The

Dark Era of the Turkmen of Tuz Khurmatu District under the Protection of the

Kurdish Parties and the Peshmerga (2003-2017) *

Sheth

Jerjis **

Journal

of The Association for the Study of EthnoGeoPolitics

(EGP) Forum of EthnoGeoPolitics Vol.12 Nos.1-2 Winter

2024

Abstract

This article seeks to provide details and revealing insights about the

difficult, indeed dire conditions experienced by the Turkmen in the district of

Tuz Khurmatu, due to the policies of the Kurdish parties and the behaviour of the Peshmerga fighters, who monopolised the administration and governance of the

district, along with other Turkmen areas, after the fall of the Ba'ath regime

led by Saddam Hussein in April 2003, for 11 years until mid-2014, and with the

Shi'ite armed factions since then until October 2017. This occurred at a time

when the Iraqi state had collapsed and the rule of law was absent, and the

Kurdish parties were the second largest force in the administration of the

Iraqi state after the international, US-led coalition forces.

The

article also examines the ethnic and sectarian composition of the Tuz Khurmatu

district, the suffering of the district's Turkmen majority under the ethnic

cleansing policies practiced by the Ba'ath regime, and the administrative and

political situation after its fall. It also discusses how Western media,

strategic centres, and human rights organisations dealt with the Turkmen presence in Iraq in

general, and with the bloody events and the suffering of the Turkmen there

during the period of study. The article concludes that the Turkmen of Tuz

Khurmatu experienced the worst period in their history, specifically between

2003 and 2014, when they were under the sole control of Kurdish parties and

were 'protected' exclusively by Kurdish security forces and the Peshmerga.

The

article argues that the Kurdish parties and the Peshmerga played both a direct

and indirect role in the violent attacks on the Turkmen, and that Western media

outlets, strategic institutions, and research centres

did not paint a true picture of those events. Instead, they relied on Kurdish

politicians and the Peshmerga to gather, provide and interpret information,

resulting in a lack of neutrality that favoured the

Kurds.

The

article also shows that the Western approach to the Kurdish issue is

superficial and biased, influenced by the overwhelming sympathy stemming from

the largely unintentional exaggeration of Kurdish suffering in Western

publications and the influence of Western political approaches. It also argues

that Western studies of the Anfal campaigns (April-May 1988) lack adherence to

scientific principles and rely entirely on Kurdish narratives, with all their

attendant exaggerations and biases. As a result, thousands of inaccurate

reports, articles and studies have emerged, portraying the operation as a fable

brutal myth.

These

criticisms target the credibility of Western strategic centres,

including the media, human rights organisations and

academic research centres, which should rightly cast

doubt on their integrity. Therefore, these Western centres

are required to review their claims regarding the number of Kurdish victims in

the Anfal campaign, which they estimated at between 50,000 and 200,000 people,

while adhering to the principles of scientific research.

Keywords Tuz Khurmatu, Kirkuk, Kirkuk, Turkmen,

violence, Kurdish parties, Islamic State, Islamic state (ISIS), Peshmerga

fighters, Iraq

Introduction

Nationalist

sentiments have dominated Middle Eastern societies since the beginning of the

twentieth century, and because Iraq has been part of this region, their impact

on the multiethnic Iraqi society has been profound. Arab nationalist sentiments

reached their peak in Iraq with the Ba'ath Party (حزب

البعث),

while Kurdish nationalist sentiments reached their peak with the launch of the

Kurdish armed movement against the Iraqi state in the early 1961. On the other

hand, nationalist sentiments among Iraq's smaller communities, the third

largest of which is the Turkmen, grew with the same momentum, prompting them to

insist on demanding their ethnic and cultural rights.

The

events that followed the fall of the Ba'ath regime in Iraq fuelled

ethnical and religious conflicts. Iraqi society is a mosaic of diverse sects

and religions. The challenges faced by Iraqi society, including racist

dictatorship, ongoing wars and an economic blockade, have exacerbated internal

divisions and conflicts. The absence of a democratic culture and system has

made smaller, less powerful communities, such as the Turkmen, who lack the

means to protect themselves and their regions, vulnerable to all forms of human

rights violations.

Iraqi

Turkmen have suffered from this situation since the establishment of the Iraqi

state in 1921. Their numbers were deliberately reduced immediately after the

declaration of the Iraqi state, and this process continues to this day—although

this intentionally reduction in their population size has been somewhat

abandoned after the fall of the Ba'ath regime. Moreover, education in the

Turkmen language was abolished in the 1930s, and their presence in state

institutions dwindled over time. The Ba'ath regime violated the most basic

human rights, extending to all Iraqi communities, with the Turkmen being the

most affected. For example, vast Turkmen lands were confiscated, the

demographic composition of their regions was altered, and they were forced to

change their ethnicity to Arab. The Turkmen's adherence to their national

culture, the oil wealth of their regions and the fertility of their lands have

been among the most important reasons why they were subjected to the injustice

of the fanatical racist nationalist powers that usurped the reins of government

in Iraq.

Shi'ite

Turkmen suffered from the Ba'ath regime's racism on both the national and

sectarian levels. Tuz Khurmatu is one of their most important areas, where

their suffering and rights violations have been widespread and ethnically

based. At the sectarian level, large numbers of the district's citizens were

arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment or death on the pretext of

belonging to secret Shiite parties. Many of them disappeared without any

information or trace of their whereabouts. Their areas were subjected to

attacks and artillery shelling by the army and armed Ba'athist militias after

the Second Gulf War in 1990 during the Sha'ban uprising. The Dutch

anthropologist Van Bruinessen observed that the

"Shiite Turkmen city of Tuz Khurmatu was destroyed" (Van Bruinessen

2005: 46).

The

fall of the Ba'ath regime in 2003 was followed by a period of chaos and

catastrophe in Iraq. The state collapsed, along with the security and military

apparatuses. Laws lost their force, security stability was completely lost, and

sectarian conflicts emerged. This coincided with the onset of various terrorist

attacks across Iraq, reflecting acutely in the Turkmen regions, as most of

these were and are religiously and ethnically mixed.

The

complete control of the Kurdish parties and Peshmerga fighters over almost all of northern Iraq immediately after the fall of the

Ba'ath regime and for more than a decade after it, posed another extreme

challenge to the Turkmen regions, no less serious than the sectarian conflicts

of the same period. The Kurdish parties claim ownership of almost all Turkmen

lands, considering these historically Kurdish lands and incorporating into the

map and constitution of the Kurdish region. This monopoly enabled the Kurdish

parties to monopolise power in Iraq immediately after

the US-led occupation, with the full support of the latter's coalition forces,

to place almost all Turkmen lands within the disputed territories, thus casting

doubt on the Iraqi and Turkmen identity of these regions (Kane 2011:

13-14,22,32,37).

General

information

Tuz

(Duz) Khurmatu is a Turkmen name meaning salt, dates, and berries, which was a

subdistrict of Kifri District in the Kirkuk

Governorate. In 1922, it became a subdistrict of Tawuq

(Daquq) in the same governorate (Edmonds 1957: 277).

In 1951, it became a district of Kirkuk Governorate. In 1976, as part of the Arabisation policy pursued by the Ba'ath regime aimed to

reduce the Turkmen population density in Kirkuk governorate, Tuz Khurmatu was

separated from the Kirkuk and annexed to the Salah al-Din governorate, despite

being closer to the central city of Kirkuk than to the central city of Salah

al-Din Governorate. Additionally, the district forms a promontory approximately

60 km eastward in relation to Salah al-Din Governorate, indicating that its

connection to Salah al-Din is political in nature. The Tuz Khurmatu district

also included the Amerli subdistrict until 2018, when

the latter became a district.

The

Tuz Khurmatu district is located 75 km south of Kirkuk governorate. The

district consists of dozens of villages and three subdistricts: Markaz, Amerli and Sulayman Bek. Amerli

separated from Tuz in 2018 and became an independent district. Tuz District had

a population of 30,000 in 1922 (Edmonds 1957: 277). In the 1957 census, the

population of the district's central sub-district, which covered roughly the

same area as today's Tuz district, was 88,466 (Principal bureau of statistics

1958: 15). In the censuses of 1977, 1987, and 1997, the population of Tuz

district was estimated at 61,744, 86,471, and 115,942, respectively (al-Bayati

2014: 60). In the 2018 estimates, the population of the district, including Amerli, was 191,729. The area of Tuz Khurmatu district,

along with Amerli, is 2,316 square kilometres (Central Statistical Organisation

2018: 278).

Ethnic

composition

Tuz

Khurmatu is considered one of the Turkmen regions least exposed to Kurdish and

Arab migration compared to many other Turkmen regions, such as the many regions

in Kirkuk Governorate and the city of Erbil city (Jerjis

2022: 76). The vast majority of Arabs in Tuz Khurmatu

are Arabised Turkmen from the Bayat Turkmen tribe,

who reside mainly in the Sulayman Bek subdistrict and some of its villages, as

well as other villages in the district. They are accompanied by a small pocket

of the Arab Albu Hamdan tribe and some other Arab tribes, particularly in the

Al-Hlewa area. The Kurds in the district live in the centre, and there are a few Kurdish villages to the east of

Tuz Khurmatu.

It

can be said that Kurdish migration westward to the Turkmen regions was

relatively smaller the further south one went. Kirkuk accounted for the largest

share, due to its economic recovery as a result of oil

extraction, while Tuz Khurmatu's share of the Kurdish immigration was smaller

than Erbil and Kirkuk's. Until the 1950s, when Kurdish migration to Kirkuk was

massive, their arrival in Tuz Khurmatu was less frequent.

After

the declaration of the republic in Iraq in 1958, Abdul Karim Qasim's government

has built neighbourhoods in many Iraqi cities, naming

these the Iskan or al-Jumhuriya

Neighbourhood. Kurds acquired most of these houses in

the Tuz Khurmatu city and the city of Kirkuk. The influx of Kurds continued

into Turkmen areas with the start of the armed Kurdish movement (الحركة الكردية

المسلحة) in the north in 1961, interspersed with periods of increasing

numbers as events unfolded, like for example:

- With the collapse of the Kurdish

movement in 1975, after the conclusion of the Algiers Agreement between Baghdad

and Tehran.

- With the Kurdish Aghas (rural notables)

selling their lands to the Iraqi government in the second half of the 1970s,

particularly from the Surji, Khailani, and Khoshnaw

tribes, this led to the displacement of large numbers of Kurdish villagers from

their mountainous regions to cities and villages in neighbouring

governorates, including Turkmen areas such as Erbil city, Kirkuk governorate,

Tuz Khurmatu district and Diyala governorate.

- With the Ba'ath government demolishing a large number of villages in the northern provinces,

particularly Kurdish ones, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which triggered

another large wave of Kurdish displacement.

- With the Anfal operations of 1987 and

1988, which were followed by the migration of larger waves of Kurds to Turkmen

districts and cities.

The

Tuz Khurmatu district had its share of these migrations. The Jamila district,

an unofficial name, emerged within the predominantly Kurdish Al-Jumhuriya neighbourhood toward

the end of the 1970s following the migration of Kurds, particularly from

villages in the Qadir Karam subdistrict in the eastern part of the Tuz Khurmatu

district.

After

the fall of the Ba'ath regime in 2003, and with the northern part of Iraq

remaining under the control of Kurdish parties and their militants, it was easy

for them to bring in thousands of families from Kurdish areas and settle them

in all Turkmen areas. They built illegal housing on municipal, government, and

Turkmen lands, and took control of all government buildings, housing Kurdish

families in these or turning these into headquarters for Kurdish parties or the

Peshmerga. The same events happened in most areas of northern Iraq,

particularly in Kirkuk governorate.

In

the Tuz Khurmatu district, Kurdish families-built hundreds of homes on a vast

expanse of land between the Al-Jumhuriya and Jamila neighbourhoods on one side and the mountains east of the

city on the other. Both neighbourhoods expanded to

several times their original size. The vast majority of

Kurdish families were not residents of the district but had migrated from the

east. When the Iraqi army entered the city on November 17, 2017, all

Kurds—families, employees, and Peshmerga—left the district in fear of

retribution and all of them returned seven to eight months later, with the exception of the Peshmerga, security forces and

employees who had abused the Turkmen.

Thus,

most of the Kurds who entered the district after the fall of the regime

remained in Tuz Khurmatu. As for the expulsion of families from Tuz Khurmatu

during the Ba'ath regime, the number of Turkmen people expelled reached in the

hundreds, while the number of Kurds expelled did not exceed a few dozen

families.

As

for the Turkmen areas in Tuz Khurmatu, the district centre,

which contains more than half of the district's population, and the city of Amerli, the overwhelming majority are Turkmen. The centre of Sulayman Bek district is home to an overwhelming

majority of residents belonging to the Arabised

Turkmen Bayat tribe, with one-tenth of the population speaking Turkmen as their

first language. Turkmen also inhabit many villages in the Amerli

district, the largest of which are Bir Awchili, Chardaghli, and Qara Naz, as well as villages in the

Sulayman Bek district, and some villages of the Tuz Khurmatu city, including

the large village of Yengija.

Thus,

although Tuz Khurmatu is considered a historical Turkmen district, and the

Turkmen still constitute the vast majority there despite significant Arab and

Kurdish migration, many Western sources err in presenting an ethnic composition

that is contrary to the reality of the population of Tuz Khurmatu. They either

present equal proportions of nationalities (Gaston 2018: 52), mention Kurds

first (European Asylum Support Office 2018: 2; Human Rights Watch 2017), or

mention Turkmen as a third nationality (International Organisation

for Migration 2024A: 1).

As

is the case in all Turkmen regions, many Western sources exaggerate the size of

the Kurdish presence in Tuz Khurmatu. For example, a Zoom News report indicates

that "the Kurdish population in Tuz Khurmatu has decreased to 30% due to the

Arabization campaign" (Zoom News 2024). However, today, after the settlement of

hundreds of Kurdish families in the district after the fall of the Ba'ath

regime, the actual percentage of Kurds in the district is much lower than the

claimed percentage (Kirkuk Now 2024).

As

for the Kurdish media, their exaggeration in distorting the facts about the

ethnic distribution of the population of the Turkmen regions in favour of the Kurds is even more pronounced. In one of its

reports, the Kurdish Rudaw media network increased

the percentage of Kurds in the district to 40% (Rudaw

2017).

There

are international reports that do confirm the Turkmen nature of the Tuz

district. A report by the United Nations International Organisation

for Migration states: "The Tuz Khurmatu district, home to Shia, Sunni Turkmen,

Sunni Kurds, and Sunni Arab communities, is strategically located on the

Kirkuk-Baghdad highway in central Iraq. The centre of

Tuz Khurmatu is Turkmen in origin. Its urban centre

is composed of Turkmen, Kurds, and Sunni Arab populations" (International Organisation for Migration 2024B: 7).

Today,

Turkmen constitute 65% of the district's population, Kurds 25% and Arabs 10%.

These proportions have been agreed upon among the district's components (Kirkuk

Now 2024). In the city of Tuz Khurmatu, the proportions are as follows: Turkmen

75%, Kurds 20%, and Arabs 5%.

Historically,

the vast majority of the names of people, villages,

plains, valleys and rivers in the Oblique Turkmen Line (Tal Afar-Badra) were

Turkmen until the early twentieth century (see Map 1 below). For example, Ali

Yazdi mentioned the names of Daquq and Altun Kopru with their Turkmen names in the fourteenth century

(Yazdi 1723: 451).

The

Ottoman Almanac dating back to the Ottoman Sultan's conquest of Kirkuk in the

sixteenth century mentions the names of people, cities, villages, rivers,

valleys and mountains all with Turkmen names (Nakip 2008: 37-47). Likewise, all

travellers who passed through the Turkmen Line for

centuries mentioned these Turkmen names.

For

example, James Claudia Rich, in his journey from Baghdad to Kirkuk, Sulaymaniya and to Mosul in 1820, mentioned almost all the

villages, towns, and districts along the way with Turkmen names. He mentioned

these names from Kifri until he headed to

Sulaymaniyah from Kirkuk: Kifri, Kör Dere, Kara Oğlan, Kız Kalası, Oniki İmam,

Eski Kifri, Çemen, Bayat

Plain, Kuru Çay, Kızıl Haraba,

Aksu River, Yenijeh, Tuz Khurmatu, Çubuk, Demir Kapı, Tawuq, Kehriz, Tawuq Çayi, Ali Saray, Jumaila, Matara, Taze Khurmatu, Laylan and Kara Hasan (Rich

1972).

The

traveller Rich visited Tuz Khurmatu in 1820 and

considered the ethnic nature of Tuz Khurmatu to be Turkmen and estimated its

population at five thousand (Rich 1972: vol. 1, 26, 33). A British political

officer who served in the Iraqi governments at the highest levels, described

Tuz Khurmatu as the most important centre of the

Qizilbash Turkmen sect in the province (Edmonds 1957: 277-278). The League of

Nations commission that determined the fate of Mosul Vilayet in the 1920s,

described Tuz Khurmatu as being entirely Turkish or Turkmen (League of Nations

1924: 38).

In

2018, a report by the United Nations Development Programme

(UNDP), supported by the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI),

listed Tuz Khurmatu as one of the largest Turkmen-majority areas in Iraq

considering that Turkmen constitute 7% of the population of the Diyala

province, stating "Turkomen comprise ca. 7% of the

population (with significant minority populations in Kifri,

Muqdadya, Jalawla and Saadiya, and Qarataba being among the largest Turkomen-majority

cities in Iraq)" (United Nations Development Programme

2018: 29).

As

for the Kurdish presence in eastern Tuz Khurmatu, it is not ancient. For

example, the Dawuda tribe constitutes the majority of Kurds in the eastern part of the district.

Abbas al-Azzawi and Edmonds estimated their presence there to be 150 years old

at most (al-Azzawi 1947: 165; Edmonds 1957: 272-273).

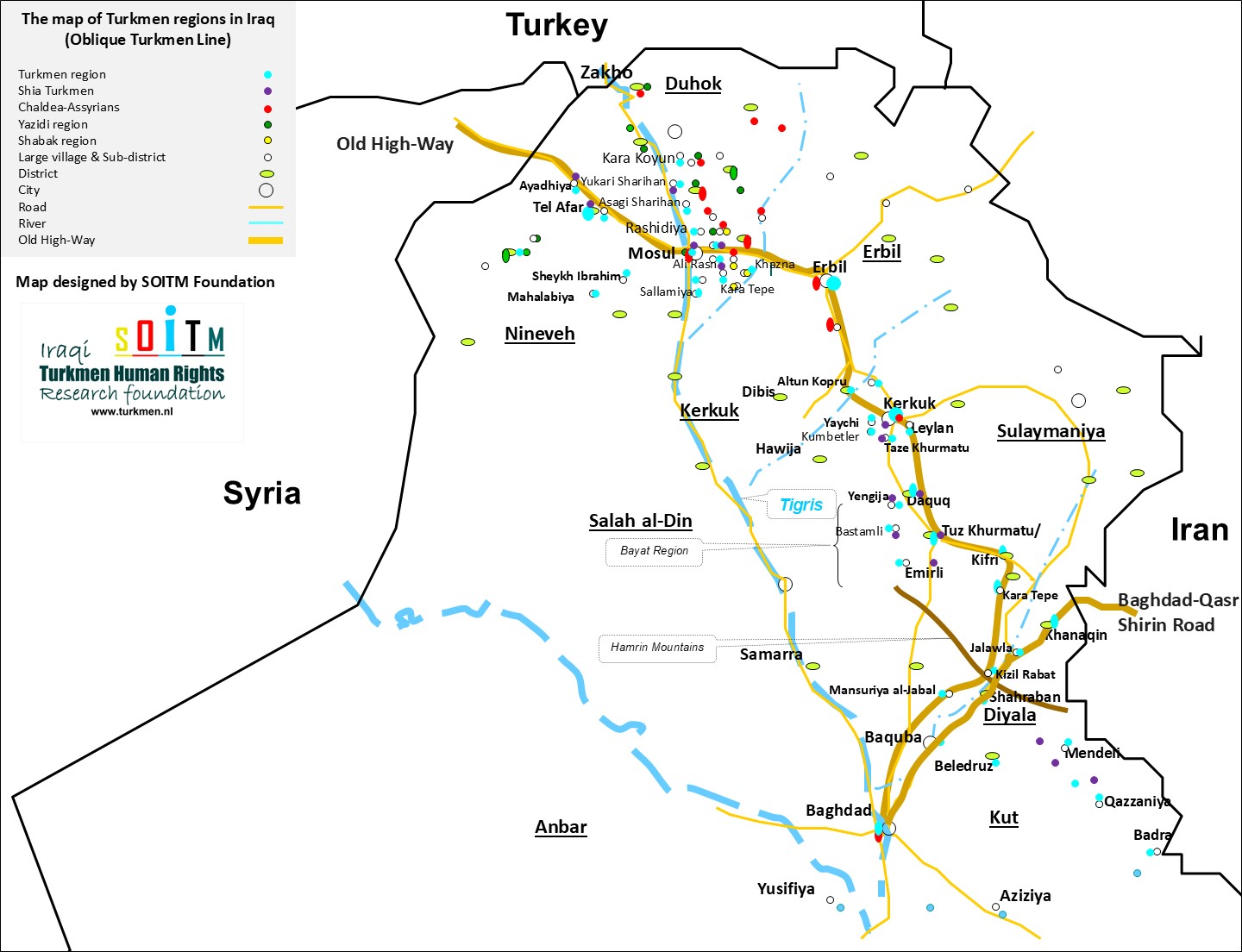

Map

1 Turkmen regions on the Oblique Turkmen Line from Tal Afar to Badra

Source: map designed by SOITM Foundation

Sectarian

structure

The

sectarian composition of Tuz Khurmatu District is as follows:

- The Turkmen in the cities of Tuz

Khurmatu and Amerli, and the villages of Bir Awchili, Chardaghli, and Qara

Naz, follow almost entirely the Shi'a sect of Islam.

- The centre of

Sulayman Bek subdistrict, many of its villages and the villages of Amerli district are entirely follow the Sunni branch of

Islam. In the large village of Yengija, Sunnis make up 80% of the population.

- The Arabs and Kurds of the district are

all of Sunni sect.

- Even so, there are always some families

of one sect in the areas of the other sect.

The

Ba'ath regime period

Before

2003, the Turkmen in Tuz Khurmatu district faced hostility from the Ba'ath

regime for two reasons: first, because they are of Turkmen origin, and second,

because the majority of them are Shia. The district

was also subject to Kurdish migration due to its location on the continuous

Kurdish migration route to the west.

Within

the framework of the racist policy that characterised

the Ba'ath regime for more than three decades, Tuz Khurmatu district, like

other Turkmen areas, was subjected to all forms of human rights violations. By

hundreds of measures, Arabisation policies included

the settlement of hundreds of thousands of Arabs in Turkmen areas, the

displacement of Turkmen from their areas, forcing them to change their

ethnicity, removing all Turkmen names for cities, villages, streets, schools,

businesses and even family names.

Hundreds

of thousands of dunums (a little more than 900 square metres)

of Turkmen land were confiscated and living conditions in Turkmen areas were

made difficult by obstructing government transactions and restricting the scope

of private businesses. Thousands of Turkmen were arrested, and hundreds of them

were executed on the pretext of belonging to political parties. This racist

policy of the Ba'ath Party was accompanied by neglect and deterioration of

urban services and infrastructure in the Turkmen areas.

In

the 1970s and 1980s, Arab neighbourhoods and

alleyways began to appear within the city of Tuz Khurmatu. The al-Tin neighbourhood and the al-Askari neighbourhood

were built for Arabs. Land was also granted to them in the Al-Asriya neighbourhood, where the government financed the

construction of homes. Similarly, homes were built by Arab families in the Imam

Ahmed neighbourhood.

As

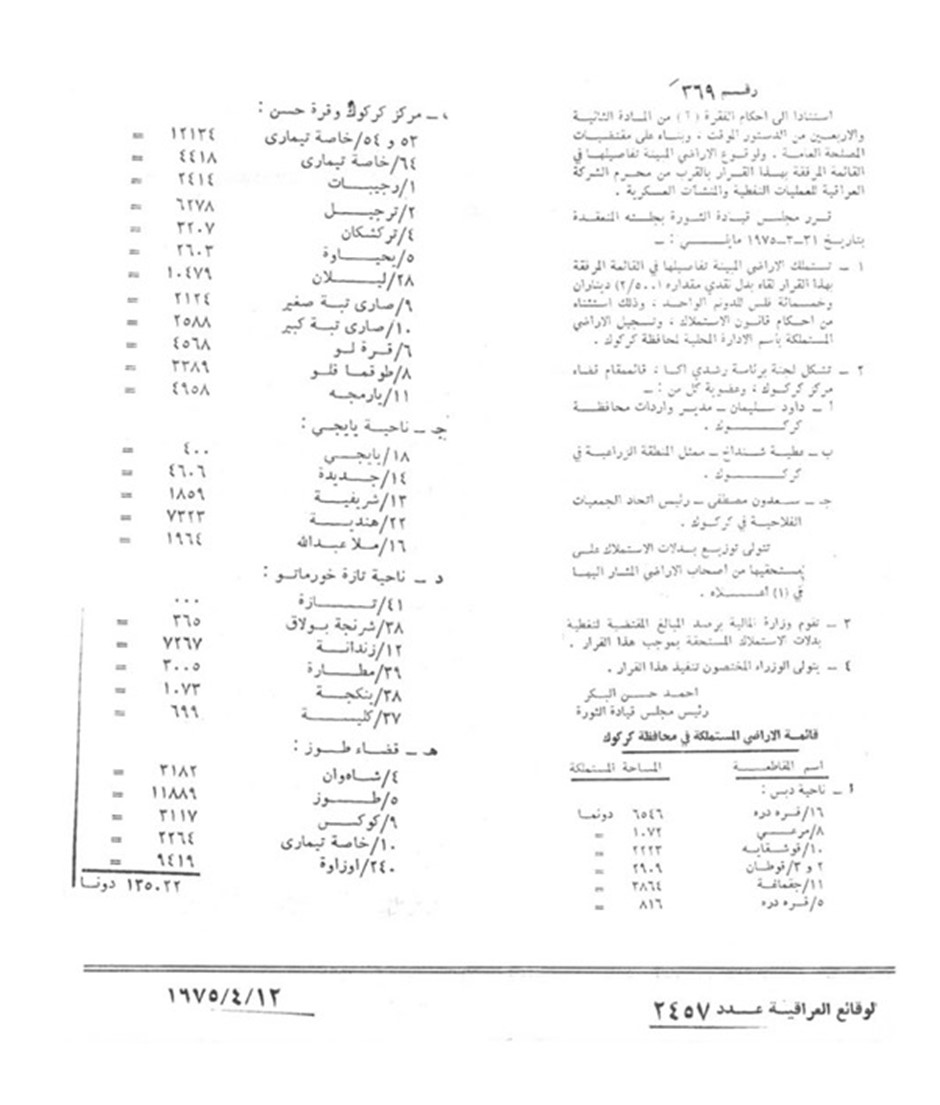

for land confiscation, by Revolutionary Command Council Resolution No. 369,

dated March 31, 1975, as part of the largest confiscation of Turkmen land in

Kirkuk Governorate, 29,871 dunums of land were expropriated in the Tuz Khurmatu

district, all of whose owners were Turkmen from the

district (see Appendix 1), as Tuz was one of the districts of Kirkuk

Governorate.

After

the fall of the Ba'ath regime, the new Iraqi government established a

governmental institution called the Property Claims Commission to resolve the

issue of confiscated lands throughout Iraq. The number of lawsuits filed by the

Turkmen of Tuz Khurmatu before this commission reached 4,970 by 2014 to 2015,

and not a single land was returned to its Turkmen owners (Unrepresented Nations

and Peoples Organisation 2013: 7).

The

Ba'ath regime regularly accused of hundreds of Tuz Khurmatu's Turkmen of being

either nationalists belonging to national political parties or Shi'a religious

parties. In a campaign of arrests that took place between 1980 and 1982,

hundreds of Turkmen were arrested for their alleged affiliation with Iraqi

Shi'a parties. As many as 101 of them were executed, while many others were

sentenced to various harsh sentences, including life imprisonment. Many

disappeared after their arrest, and many Tuz Khurmatu residents left Iraq for

fear of persecution and death (Islamic Union of Iraqi Turkmen 1999).

With

the withdrawal of the Iraqi army from Kuwait in March 1991, local

residents took control of the administration in most Iraqi provinces.

Ba'ath Party leaders were arrested, and their headquarters, as well as those of

the Popular Army, security services, and police stations, were attacked, with

many wounded and killed.

During

this upheaval, Turkmen youth gathered in groups in the city of Tuz Khurmatu,

particularly from the neighbourhoods of Mulla Safar,

the Kuchuk Mosque area and the Tanki neighbourhood.

They armed themselves and began writing and distributing leaflets to homes and

shops, taking control of the intelligence and postal offices.

Contact

was made with some Kurdish groups, and on the evening of March 11, 1991, most

of the city's districts were seized, including the main police station, the

security office, and later the Popular Army (الجيش

الشعبي) headquarters. Turkmen armed youth set up guard posts on the

outskirts of the city and prevented Kurdish militants from attacking

educational institutions. Thefts then spread to state institutions by Kurdish

groups and sometimes by residents of the city itself.

The

city had been subjected to artillery and mortar shelling, and occasional aerial

bombardment by the Ba'athist forces and paramilitary loyalists for more than a

week since the uprising began. The city was then stormed. The Iraqi army and

Arab tribes overcame the resistance of the city's residents, entered the city

and suppressed the uprising after residents were threatened with chemical

weapons attacks following a demonstration by warplanes across the city's skies.

The city was also bombed before and during the assault, killing and wounding

dozens of residents and damaging many homes.

On

the first day of the government regained control of the city, all residents

were evacuated. When they returned to the city more than a week later, many

found their homes or shops empty and their cars stolen, having been looted by

the Popular Army and members of the Arab tribes. The army had arrested

approximately 500 young Turkmen, most of whom were assaulted and imprisoned.

Many armed Turkmen who resisted the army fled to neighbouring

countries for fear of retribution.

After

the fall of the Ba'ath regime

This

phase began with the overthrow of the Ba'ath regime on April 9, 2003, through

US military intervention. The Coalition Provisional Authority was then formed,

headed by Paul Bremer, who was directly linked to the US Secretary of Defense

as the governor of Iraq. Immediately after the fall of the Ba'ath regime, all

Iraqi state institutions being staffed by Ba'ath Party members were dissolved,

including the civil administration, security forces, and army (Baker 2003: 4)

Within

the framework of the strategic partnership between the United States and

Turkey, the United States was confident of Turkish support for the overthrow of

the Ba'ath regime in Iraq in 2003. However, the United States was disappointed

when Turkey refused to participate and did not allow the use of Turkish

territory. The United States then replaced Turkey with the Kurdish parties as

its sole strategic partner in Iraq.

The

Kurdish parties and Peshmerga forces became the second largest force after

those of the United States in administering Iraq and in rebuilding the Iraqi

state and its new institutions, having received full support from the United

States. The Kurdish parties came to dominate the mechanisms of governance in

Iraq. The Kurdish Peshmerga fighters became the equivalent of the Iraqi army

and took control of northern Iraq. Thus, all Turkmen and other minority areas

in Iraq came under Kurdish control. The region remained under the absolute

administrative, security, military, and economic control of the Kurdish parties

for fourteen years, until 2017.

All

non-Kurdish parties, including Arab, Turkmen, and Assyrian parties, were

founded abroad, with the exception of the Iraqi Dawa

Party; all of those parties lacked experience in governing a state even on the

local level or operating as a professional opposition. The Kurdish parties,

however, had thirteen years of experience in governing their regions and had

established their own security and military forces, represented by the

Peshmerga and the Asayish (Kurdish security).

The

Kurds have long enjoyed excessive sympathy from the West, particularly because

they were subjected to attacks from the states they fought, particularly in

Iraq. This was reflected in the substantial financial, logistical, political,

and media assistance provided to the Kurdish parties and Kurdish society, while

ignoring other Iraqi communities, the largest of which were and are the

Turkmen.

In

short, after the fall of the Ba'ath regime, the state's administrative,

security and military institutions had collapsed and remained so for a

considerable time, the rule of law was absent, chaos was rampant

and violence was prevalent throughout Iraq. Kurdish parties and the Peshmerga

had come to dominate the Iraqi political scene. Under these trying and

harrowing circumstances, the construction of a new Iraq began from scratch,

including the drafting of a new constitution.

General

situation

When

the Ba'ath regime fell, the same things happened in Tuz Khurmatu as happened in

most of Iraq. In Tuz Khurmatu, particularly the Kurdish Peshmerga and Kurdish

security forces looted all government offices and emptied them of their

contents. They seized control of all government buildings, turning these into

headquarters for Kurdish political parties or the Peshmerga. Kurdish forces

arrested many Turkmen and expelled others from government offices, claiming

they were members of the Ba'ath Party and who had wronged some Kurds before the

occupation.

In

northern Iraq, Arabs were politicised

nationalistically and well-organised partisanly and

being prepared to resist any force that would deprive them of the enormous

gains granted by the Ba'ath regime. They were also prepared to defend

themselves against any potential attack, especially by Peshmerga fighters,

given their role in the Ba'ath Party and the Arabisation

of Kurdish, Turkmen, and other minority areas.

As

for the Kurds, their parties and armed Peshmerga gained control of northern

Iraq, as well as much of the Iraqi political arena and the Iraqi government.

They have a strong desire to establish a Kurdish state in northern Iraq—and are

prepared to avenge the injustices they suffered at the hands of the Ba'ath

regime. They consider most of northern Iraq, especially the Turkmen regions and

areas with other minorities, to be historically Kurdish regions. Thus they include these among the disputed territories, registering

these in their constitution, and including these on their maps.

The

Turkmen and other Iraqi minorities, most of whose territories are located in northern Iraq, were eager to redress the

injustices they suffered at the hands of the Ba'ath regime and to obtain their

cultural and national rights. They feared the control of the Kurdish parties

and the co-optation of their regions. The slightest administrative, political,

economic and security measures taken against them or with disadvantageous

effects for them became a source of resentment among Sunnis, Turkmen and other

minorities toward the state led by Shia and Kurdish parties. Tuz Khurmatu was

one of the areas that met all of the afore-mentioned

conditions.

The

administration

The

Ba'ath regime subjected Tuz Khurmatu district to continuous oppression and

repression. The district housed the headquarters of political parties and the

armed popular army, as well as police and intelligence departments, where Arab

Ba'athists constituted the majority. The people of Tuz Khurmatu lived in

anxiety and suspicion under Ba'ath administration, lacking even the most basic

weapons to protect themselves in emergency situations. As was the case

throughout Iraq, all state institutions in Tuz Khurmatu were run by Ba'athist

cadres with high party ranks.

The

decision of making the De-Baathification Commission, issued by the US civil

administrator and then-President of Iraq, Paul Bremer, at the insistence of

Iraqi political parties, particularly the Shi'ite ones, just days after the

fall of the Ba'ath regime on April 16, which took effect on May 16, 2003,

played a major role in the disintegration of the Iraqi state. Therefore, it was

necessary to form new administrative cadres for the state across all its

institutions.

Tuz

Khurmatu fell to Peshmerga forces led by American soldiers in April 2003. A few

days later, a Kurd was appointed as Tuz Khurmatu's new mayor. Shortly

thereafter, American officers met with figures from the district's Turkmen,

Kurdish and Arab communities, informing them that a new council would be formed

to administer the district, consisting of nine members, three from each

community. The Kurd representatives requested four, one more than the other

communities, a request rejected by the Turkmen and Arab representatives. At the

same time, the Arabs generally were reluctant to participate in the process.

Ultimately,

it was agreed that the council would have twenty-one members, seven from each

community, despite the Turkmen having a greater claim as the majority in the

district and the region being known for its Turkmen identity. This was similar to many Turkmen-majority areas and other regions in

northern Iraq where the rights of the Turkmen majority were deliberately

downplayed and ignored. This situation was repeated in the 2005 provincial

council elections. Since all Iraqi general and local elections in the Turkmen

regions were held under the absolute control of the Kurdish parties and the

Peshmerga, and in the absence of security stability, the Kurds achieved results

far superior to their actual presence in all areas of northern Iraq (see Table

1 below).

American

officers supervised the formation of the new council in the district. It was

agreed that the council presidency would be assigned to a Turkmen. The Turkmen

Front intervened and imposed its own particular candidate

for the presidency. However, the Kurds and Arabs rejected this Turkmen

candidate, claiming that he was an active member of the Ba'ath Party, and

demanded another candidate. But the Turkmen Front did not withdraw its

candidate, and it was decided to hold elections for the council presidency.

The

Kurds and Arabs agreed, as some of the council members were Arabs chosen from

among those close to the Kurds. They elected an Arab to the presidency, and an

American representative attended council meetings. A Kurd from outside the

police force was appointed director of the judicial police, and the Kurds took

control of all state institutions in Tuz Khurmatu.

Although

the directors of some departments were Turkmen, they were under the control of

the Kurdish administration. Later, when it was necessary to appoint people to

sovereign positions in the judiciary, the Judicial Council would send three

names, one from each ethnic group to the relevant ministry, and in most cases,

the Kurdish name was approved. This administrative structure remained largely

unchanged until the Iraqi army took control of the district in 2017

(Derzsi-Horvath 2017; Note 1).

So

immediately after the fall of the Ba'ath regime, the Kurdish parties and the

Peshmerga appointed large numbers of Kurds from outside the city to government

offices, especially in the health and education directorates, and they became

the overwhelming majority in the police department. The Kurdish Security

Directorate (Asayish) formed the security apparatus

consisting almost exclusively of Kurds, and the Peshmerga became the army of

the district.

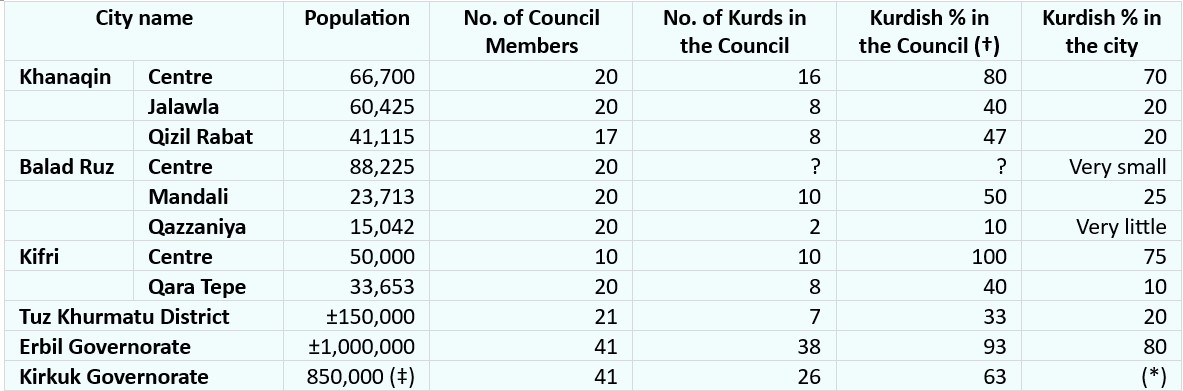

Table

1 Various estimates of the Kurdish

population in various areas along the

Oblique Turkmen Line after the fall of the Ba'ath regime *

Table

*

Table 1 intends to illustrate the increase in the number of Kurdish members in

municipal councils in those areas relative to the size of the Kurdish

population.

(†)

Percentage of Kurds in district and subdistrict councils according to

appointments under the supervision of the American military, Kurdish political

parties, and Kurdish Peshmerga that took place in 2003, and in provincial

councils according to the elections that took place in January 2005.

(‡)

Population of Kirkuk governorate during fall of the Ba'ath regime in 2003

(International Crisis Group 2006: 2).

(*)

There are no reliable statistics or estimates.

Military

and security forces in the district from 2003 to 2017

Kurdish

Peshmerga

From

the first day after the fall of the Ba'ath regime, Kurdish parties controlled

the vast majority of northern Iraq and large parts of Diyala and Salah al-Din

provinces (Kane 2011: 9, 14-15). The Peshmerga were the sole military force in

these vast territories, and the police and security services were subordinate

to the Kurdish parties. There were three Peshmerga brigades in the Tuz Khurmatu

district, and the Kurdish parties controlled the security and police services.

With

the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) (الدولة

الإسلامية في العراق

والشام) occupation of eastern Tuz Khurmatu in 2014, the Kurdistan

regional government deployed an additional fourth brigade of Peshmerga fighters

to Tuz Khurmatu, claiming to bolster security in the area. However, just as the

other three Peshmerga brigades deployed in the area did not provide protection

for the Turkmen, the deployment of the fourth brigade did not.

Federal

police

As

attacks on Turkmen in the region increased by ISIS, with bombings sometimes

reaching as many as 24 per day, the Iraqi government deployed a federal police

(الشرطة الاتحادية) regiment in 2011 despite opposition and

threats from Kurdish parties and the Peshmerga. The federal police were

stationed in the Silo area outside the city, but they were subjected to

frequent harassment by the Peshmerga.

The

presence of the federal police did not mitigate attacks on the Turkmen; rather,

it increased the bombings. When ISIS took control of the western part of the

district, Peshmerga forces attacked the Federal Police headquarters, expelling

them from the district and seizing their vehicles and weapons, including tanks.

During the same period, the Peshmerga also expelled Baghdad-backed forces in

Kirkuk governorate. Under the control of the security apparatuses affiliated

with the Kurdish parties and the Kurdish Security Service (Asayish-اسايش), the Kurds rejected the Turkmen parties' persistent requests

and strenuous efforts to establish armed Turkmen factions to protect themselves

and their areas.

Iraqi

and Turkmen Shi'a armed factions

The

Kurds continued to refuse the entry of the Iraqi army and any other armed

faction into Tuz Khurmatu, despite the genocide being continued committed

against the Turkmen by ISIS. The fatwa issued by the Shia religious authority,

Ali al-Sistani, in Najaf in mid-2014 calling for the formation of a popular

army made the Kurds accept formation of Turkmen Popular Army factions. The

siege of Amerli by ISIS, which became an

international issue, forced the Kurdish parties to accept the entry of Shiite

factions into Tuz Khurmatu. In June 2014, Asaib Ahl

al-Haq, Hezbollah, the Badr Organisation, and Saraya

al-Salam entered the district.

The

new Iraqi army

The

Iraqi armed and security forces were largely politicised

and partisan under the Ba'athist state, and completely disintegrated with the

fall of the regime, leaving the entire Iraqi society in a state of complete

insecurity amidst political, sectarian and ethnic instability. Rebuilding the

Iraqi army and security services took many years, and these still suffer from a

lack of professionalism and administrative and military problems.

As

it is mentioned elsewhere, with the advent of the new era, and for years, Kurds

played a major role in establishing and filling positions in the new military

institutions. For example, starting with assuming the positions of Chief of

Staff of the Army and Commander of the Air Force, they also had a significant

presence in the new military divisions formed in Mosul, where a large number of unqualified Kurds were appointed as

soldiers and commanders, most of whom were Peshmerga (Mahdi 2013). After nearly

14 years, the Iraqi army wrested control of all areas of northern Iraq from the

Kurdish parties and the Peshmerga, with the exception of

the three Kurdish provinces, in October 2017.

Sectarian

and nationalist violence (2003-2017)

After

the fall of the Ba'ath regime, all conditions were ripe for sectarian and

nationalist violence. The state collapsed administratively, security-wise, and

militarily, primarily due to the United States' mismanagement of the overthrow

of Saddam Hussein's dictatorship and the subsequent administration of Iraq, the

rule of law disappeared, and marginalised Islamist

Shiite and Kurdish parties assumed leadership of the government and state. The

Ba'athists were numerous and intellectually and militarily armed. They began

exploiting nationalist and sectarian sentiments immediately after the fall,

having inflamed them to the maximum extent during their rule. Almost all

Turkmen areas, including Tuz Khurmatu, had a mixed sectarian and ethnic

character.

Sectarian

violence began immediately after the fall of the regime. In the first months

after the fall of the Ba'ath regime, two incidents in the cities of Tuz

Khurmatu and Kirkuk confirmed Turkmen suspicions that the Kurdish parties

intended to control and contain their areas and suppress any attempts to oppose

the dominance of the Kurdish parties and the Peshmerga in their areas. These

incidents also added momentum to the sectarian and ethnic conflict.

On

August 20, 2003, Kurdish Peshmerga gunmen, who controlled the district, blew up

the Mursi Ali shrine, a holy site for Shiite Turkmen in Tuz Khurmatu (Mufti

2017). The next day, groups of Turkmen held a peaceful demonstration in the

city centre, but Peshmerga forces attacked the

demonstration and opened fire, killing five Turkmen and wounding many others.

The following day, other peaceful demonstrations took place in Kirkuk in

support of the Turkmen of Tuz Khurmatu. Peshmerga forces also attacked them, killing

some Turkmen demonstrators and wounding many others.

These

two incidents in Tuz Khurmatu and Kirkuk were among the first terrorist

bombings against religious shrines and killings of peaceful protestors,

igniting sectarian and ethnic strife in Iraq. Sectarian violence quickly spread

throughout Iraq, in the absence of law and order and state institutions.

Then

came the bombing of the two major Shia shrines in Samarra on February 22, 2006.

Violence in Iraq escalated even further. All Turkmen areas, especially the Shia

Turkmen areas south of Kirkuk, which also includes the Tuz Khurmatu district,

were subjected to the largest and most violent explosions in Iraq. The Kurdish

Peshmerga forces were the only force protecting the region, dominating and

controlling it completely.

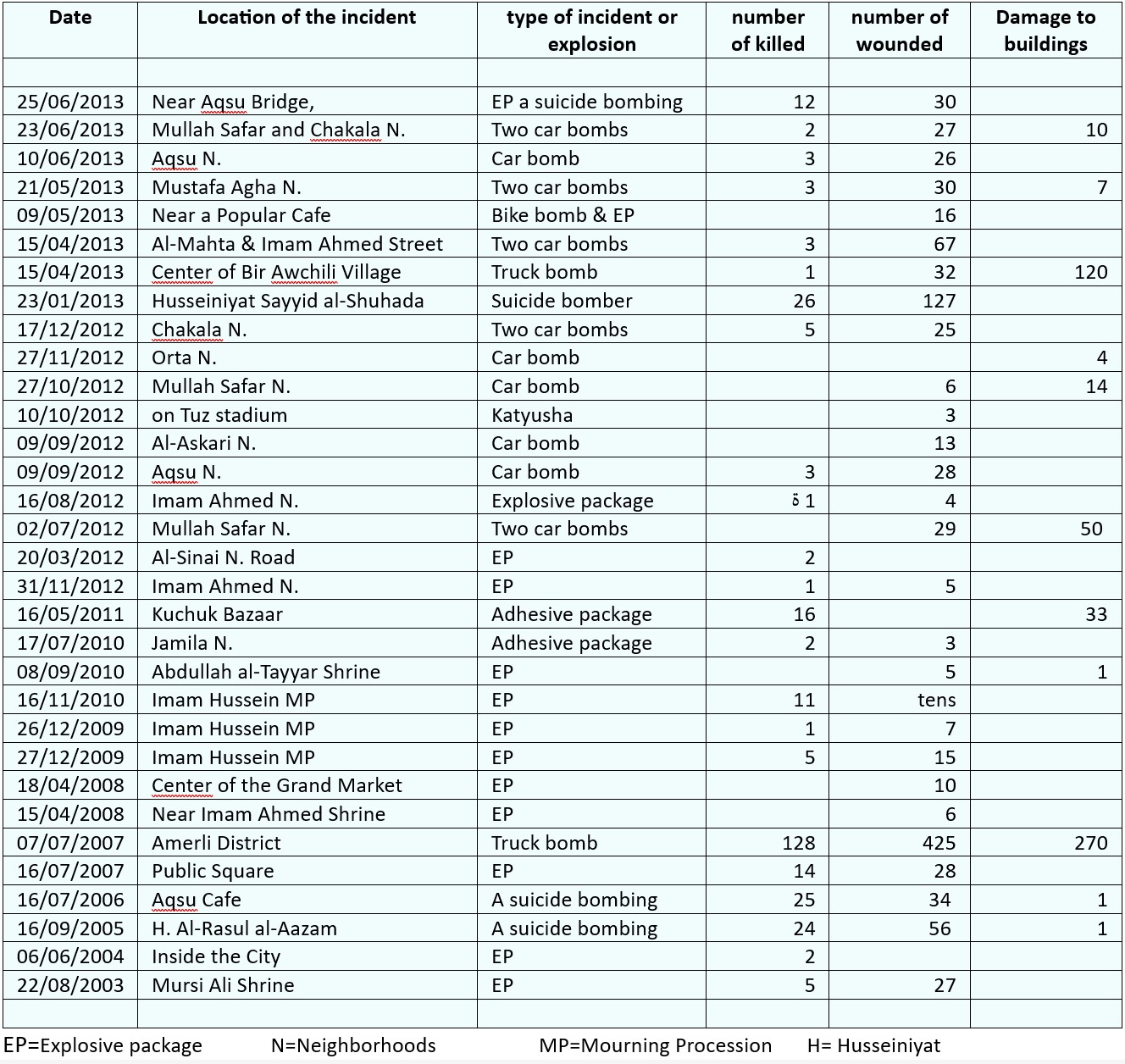

Violence

rapidly increased in the Tuz Khurmatu district; the number of explosions was

estimated at several per month during the first post-Ba'athist years, including

massive explosions in the village of Yengija and the district's city of Amerli. This later increased to several explosions per

week. By the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, explosions

had become daily, sometimes multiple times a day. They increased dramatically

with the increase in ISIS activity in the western part of the district and, at

the same time. By the beginning of the second decade, the number of daily

explosions sometimes reached dozens. The explosions were accompanied by

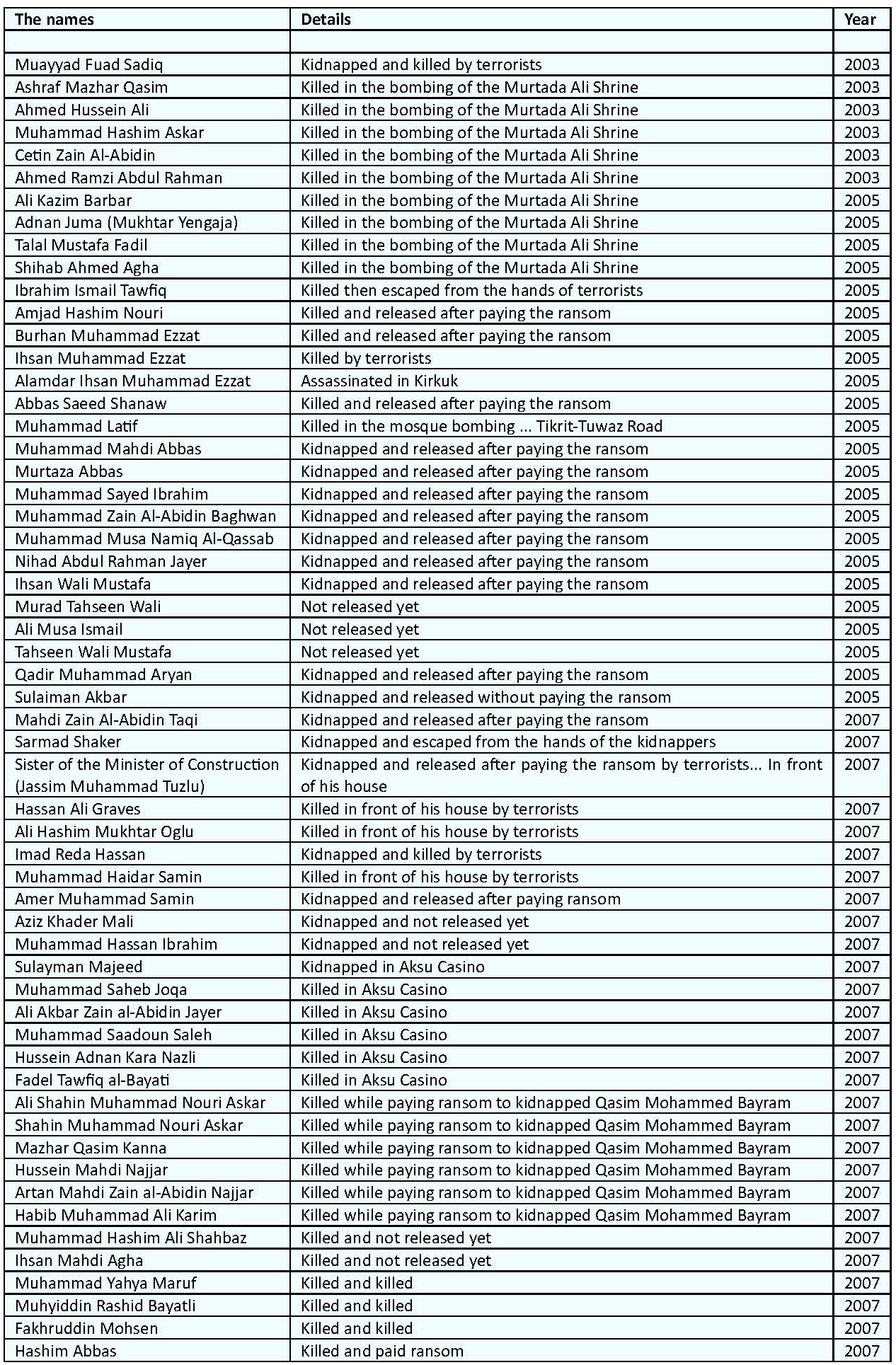

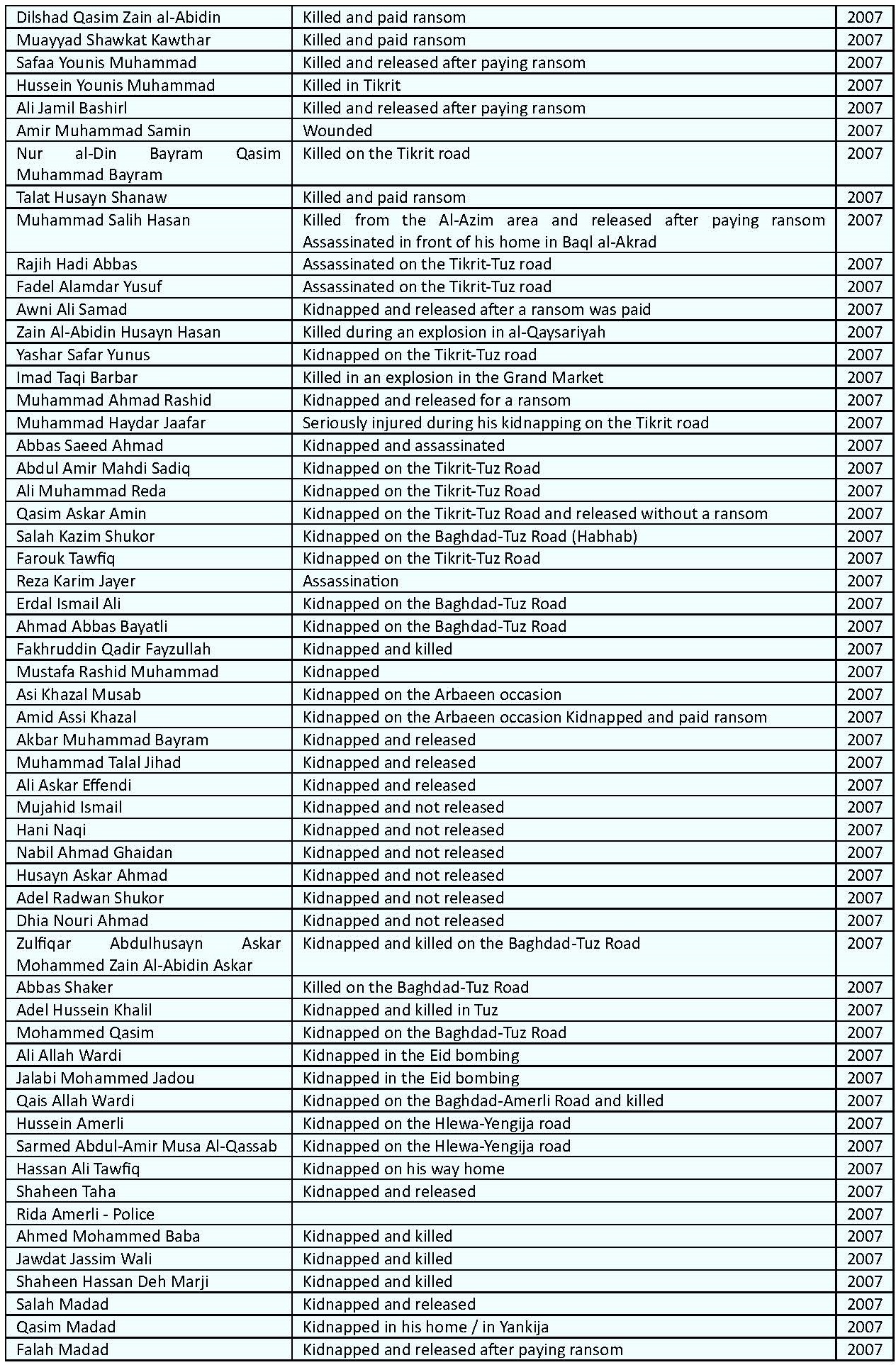

assassinations and kidnappings of Turkmen (see Appendix 3).

The

psychological state of the district's Turkmen was in shambles. During one of

the sit-ins held by the people of Tuz Khurmatu under the title "Tuz Khurmatu is

calling... Is there a helper to help us?" in front of one of the largest

religious shrines in the city of Karbala. In an attempt to draw the attention

of Shiite religious authorities to their tragedy, one of the sit-in organisers said: "We are holding a sit-in today next to

Imam Hussein so that the world may know the extent of our suffering and concerns

that have been hidden from public opinion and ignored even by those closest to

us for unknown reasons" (Ruwaih 2013).

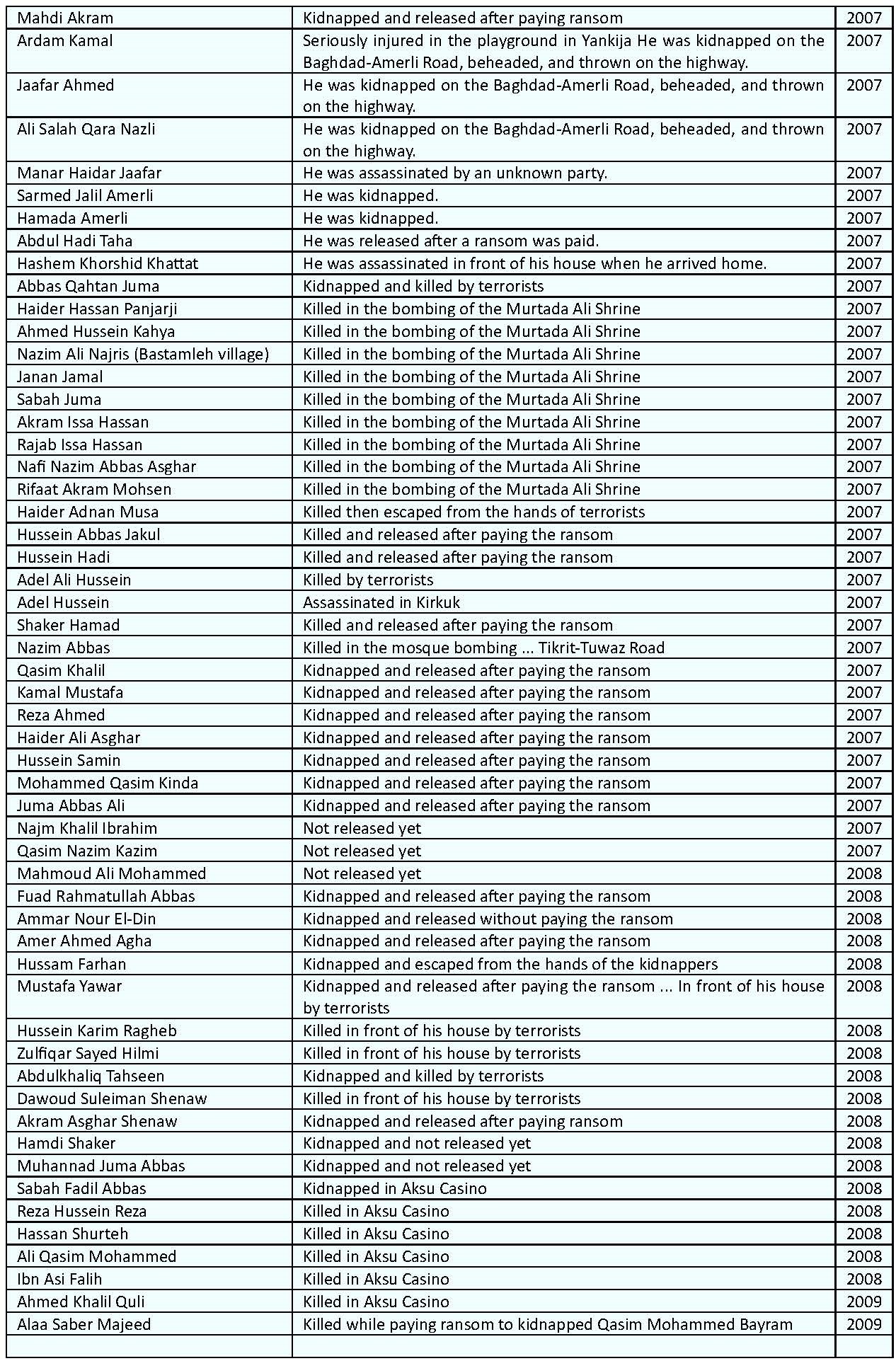

Appendix

II shown further below contains detailed information on some of the hundreds of

terrorist attacks targeting Turkmen areas in Tuz Khurmatu district. Appendix

III includes the names of a large number of Turkmen

who were killed, assassinated, or kidnapped in Tuz Khurmatu between 2003 and

2009 alone, a number that doubled several times between 2010 and 2014. Many of

the assassinations occurred in front of their homes or shops, and most of the

kidnappings took place outside the city while residents were traveling. Some

were aimed at extorting large ransoms from the kidnapped person's family. For

example, Turkmen in Kirkuk governorate paid approximately $50 million to secure

their kidnappers' release (SOITM Foundation 2019: 86; Mufti 2015).

The

Turkmen Rescue Foundation estimated the losses of the Turkmen of Tuz Khurmatu

between 2003 and 2014 at approximately 600 dead, mostly men, 3,600 injured,

including women and children, 160 kidnapped and 1,500 families displaced from

the district. The number of homes and shops demolished or closed reached 1,200

homes and 200 shops (Note 2). The 2018 report of the Iraqi High Commission for

Human Rights estimated the number of Turkmen disabled in the district as a result of bombings at approximately 1,670 people (Iraqi

High Commission for Human Rights 2018: 9). An official from the Turkmen Front

office in Tuz Khurmatu estimated the number of families displaced from the

district to safe areas in 2013 alone at 500, saying "There is no worse place in

the world for Turkmens than Tuz" (Zurutuza 2014).

All

areas of Tuz Khurmatu district suffered from massive bombings, indicating the

systematic targeting of Turkmen areas. The following incidents concern some of

the major bombings:

- The Great Mosque explosion in Tuz

Khurmatu 2005

The

explosion of the Great Mosque in Tuz in September 2005 was one of the major

terrorist attacks at the time, killing at least eleven people and wounding

twenty-five others (Al-Jazeera 2005). The Euphrates News Agency put the death

toll in the Great Mosque explosion at 24 dead and 56 wounded, with the mosque completely destroyed (Buratha News

Agency 2013).

- The assault on the village of Yengija in

2006

The

village of Yengija, located 10 to 15 kilometres

southwest of Tuz Khurmatu, was subjected to constant harassment by the Iraqi

National Guard at the time, which was largely composed of Peshmerga forces. On

the evening of March 10, 2006, the National Guard surrounded the village and

shelled it indiscriminately with rifles and mortars. By midnight, the village

was stormed. Peshmerga forces ordered people via mosque loudspeakers to remain

in their homes or they would be shot if they left. The operation lasted

approximately 24 hours.

During

the indiscriminate shooting of the village, two persons (aged 32 and 26) were

killed and nineteen people were injured. The village's water and electricity

sources were the first to be attacked. Almost all of

the water tanks on the roofs of houses were shot at and punctured. Generators,

electricity cables, and poles were destroyed. Two houses were severely damaged,

and six others were partially destroyed. Private cars, motorcycles, and

tractors belonging to villagers were shot at in front of houses (SOITM 2006).

- Aksu Café bombing in 2006

On

June 16, 2006, a suicide bomber detonated an explosive device inside the Aksu

Café in the district, killing 25 people, wounding 34 and completely

destroying the café (Buratha News Agency

2013).

- Amerli bombing

in 2007

In

one of the largest terrorist attacks in Iraq's history since 2003, a truck bomb

exploded in a popular Bazar in the centre of Amerli sub-district, which was then part of Tuz Khurmatu

(now Amerli district), on July 7, 2007, killing

approximately 160 people and wounding 240 others (al-Jarida 2007: 18).

- Taza Khurmatu bombing in 2009

Taza

Khurmatu is a large Shiite Turkmen village located outside Tuz Khurmatu

district, located between it and the city of Kirkuk. It was also under the

'protection' of the Kurdish Peshmerga. On June 20, 2009, a truck bomb exploded,

killing 73 people and wounding 200, including women and children. It also

destroyed approximately 30 homes (al-Ansary 2009).

- Husseiniyat

Sayyid al-Shuhada bombing in 2013

On

January 23, 2013, a suicide bomber wearing an explosive belt detonated an

explosive device inside the Sayyid al-Shuhada Husseiniyat

(Mosque) itself, killing 42 people and wounding 45 others.

The

period of the Turkmen and Iraqi Shi'a armed factions (2014-2017)

The

Turkmen remained disarmed and exposed to daily terror until 2014. In the middle

of that year, the Islamic State (ISIS) swept through all the villages and the

Sulayman Bek district, south of Tuz Khurmatu. However, it was unable to enter

the city of Tuz Khurmatu, besieging Amerli city on

June 11, 2014. After fierce and unequal resistance to the attacking force,

which possessed various transport vehicles and tanks, the residents of Shi'ite

villages, such as Bir Awchili, Qara Naz, and Chardaghli, took refuge in the city of Tuz, and some of

them in the city of Kirkuk (Hauslohner 2014); at

least twenty-six people were killed, and ISIS forces entered the villages and

inflicted great destruction on them.

Despite

this, the Kurds continued to refuse to allow the Iraqi army or any other armed

group to enter the district to help fight ISIS and protect the Turkmen, until

al-Sistani issued a fatwa authorising the formation

of the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF) (قوات الحشد

الشعبي) on June 13, 2014. This time, the Kurdish parties and Peshmerga

were unable to prevent the Turkmen of Tuz Khurmatu from forming armed groups to

defend themselves and their region.

The

siege of Amerli became an international issue, and

international public opinion became more concerned with saving it from falling

into the hands of ISIS in the region. At that point, the Kurdish forces were

unable to prevent the entry of armed Shi'a factions into the Tuz Khurmatu

district. In mid-June 2014, armed factions from Asaib

Ahl al-Haq (League of the Righteous), Hezbollah (Party of God), Badr organisation, and Saraya al-Salam (Peace Companies) entered

the district via the eastern Kifri district, where

ISIS militants were targeting the main road between Tuz Khurmatu and Baghdad.

Shi'a

party factions arriving in Tuz Khurmatu were able to lift the siege of Amerli, leading to the rapid collapse of ISIS. The western

part of the district and its villages were liberated within a few weeks.

Turkmen factions, formed in Tuz district based on the fatwa of al-Sistani,

joined the Shi'a party factions in the fight against ISIS. The security

situation required the Turkmen and Shia factions to remain in the district.

ISIS's

brutal control of many of the district's villages, and its subsequent defeat,

and the sectarian animosity it instigated, had extremely painful consequences

for the district. Many people were killed and wounded, and many homes and

shops, sometimes entire alleys, were destroyed. The villages had been

completely emptied of their Shi'ites when ISIS arrived, and then of their

Sunnis when they were liberated by Shi'ite factions. Many villages remained

empty for months and years, and a large number of

residents have not returned to their villages to this day.

Under

the new reality, the security situation in the district has improved, and

attacks on Turkmen declined significantly, though some bombings still occurred:

- On August 29, 2014, ISIS shelled the

military neighbourhood in Tuz Khurmatu, killing five

people and wounding twenty-five others, including five women and six children.

- On July 25, 2015, at least twelve people

were killed when two suicide bombers attacked a crowded swimming pool in Tuz

Khurmatu.

- On October 22, 2015, a car bomb exploded

outside a Shiite Mosque in the city, killing five people and wounding 40

others.

- On December 12, 2017, a mortar attack on

the city centre killed civilians in central Tuz

Khurmatu.

- On November 21, 2017, at least 23 people

were killed and 60 others wounded in a suicide bombing in the city.

Resentment

and discontent among the Kurdish parties and the Peshmerga over the presence of

Shiite and Turkmen armed factions in the district became a source of ongoing

tension, leading to three major clashes between the Peshmerga and Turkmen armed

factions between 2014 and 2017.

The

first major clash occurred on October 16, 2015, when Kurdish Peshmerga forces

opened fire on a group of Turkmen belonging to the armed factions from the

village of Chardaghli as they passed through a

checkpoint at one of the city's entrances, killing three-five Turkmen. In

response, armed Turkmen attacked a Peshmerga detachment, killing several of

them.

Clashes

spread throughout Tuz Khurmatu, with Kurdish peshmergas burning five to ten

Turkmen homes in the Aksu neighbourhood, and Turkmens

burning Kurdish shops in several Turkmen neighbourhoods.

Peshmerga forces then burned approximately thirty Turkmen homes in the al-Barid

neighbourhood. A number of

armed Kurdish stormed the home of Turkmen writer and politician Cevdet Kadioglu and forcibly took him away in front of his family.

His fate remains unknown to this day. The religious authority and Shiite parties

then intervened, calming the clashes, which had lasted for two days (Imamli 2015).

The

second major clash occurred as a result of the

Peshmerga's continued harassment of citizens in Turkmen neighbourhoods,

particularly by a well-known gang in the city led by a Kurd named Goran, who

extorted money from the city's wealthy Turkmen. At a time when the Kurdish

political parties and security forces were still firmly established in the city

centre, in the heart of the Turkmen areas, the

clashes erupted.

On

November 15, 2016, the Peshmerga shelled the headquarters of the Turkmen armed

factions, killing eight people. On the same day, the Peshmerga shelled the

Shiite endowment with tanks, prompting similar responses from the Turkmen

factions. The clashes continued for a day and a half, after which some kind of a reconciliation was reached. However, the

situation remained tense between the two sides, marred by minor incidents until

coming of the Iraqi army in October 2017.

The

third major clash between Turkmen factions and Peshmerga occurred when the

Iraqi army entered the city on October 17, 2017. Peshmerga, police, and Kurdish

security forces confronted the Iraqi army and attacked Turkmen neighbourhoods at the same time. According to some

witnesses, hundreds of shells fell on Turkmen areas, killing at least five

Turkmen and wounding about thirty others. Dozens of Turkmen homes were also

burned.

Shi'ite

armed factions cooperated with the Iraqi army to secure the central

government's control of the district, and the Turkmen burned some Kurdish

homes, in addition to about thirty homes belonging to the Goran gang. As it is

mentioned elsewhere in this article, all Kurds left the district after entering

the Iraqi army in it, and the Kurdish neighbourhoods

were emptied. The Iraqi army captured about twenty Peshmerga and handed them

over to Kurdish parties.

In

October 2017, the Iraqi army entered all of northern

Iraq and expelled the Kurdish parties and Peshmerga from them, with the

exception of the three governorates within the Kurdish region.

The

role of Kurdish parties in the tragedy of the Turkmen of Tuz Khurmatu

Many

Turkmen residents, intellectuals, and politicians in Tuz Khurmatu believe that

the Kurdish administration played a direct role in this dark period their

district experienced between 2003 and 2017. In addition to turning a blind eye

to attacks by Sunni extremists and ISIS against Turkmen, there is reasonable

speculation that Peshmerga and Kurdish security forces played a direct role in

the attacks, assassinations and kidnappings targeting Turkmen in Tuz Khurmatu.

As for the plausible reasons for these speculations:

- The Kurds had exclusive control over the

district, particularly the city of Tuz Khurmatu, administratively, militarily,

and security-wise.

- Three Peshmerga brigades controlled all

entrances to the city then the fourth came in 2014.

- The entire security apparatus and police

forces in the district were Kurdish and under Kurdish administration.

- These Kurdish forces surrounded the city

from all sides, set up checkpoints and monitored all the entrances and exits of

the city.

- All explosions occurred in the Turkmen neighbourhoods of the city only.

- The Kurdish politicians and

intellectuals have an unbridled desire to establish a Kurdish state in northern

Iraq at any cost.

- Kurdish politicians and writers consider

most of northern Iraq, including all Turkmen areas, to be historically Kurdish

regions and part of their historic homeland, Kurdistan (Kane 2011: 13-14).

Kurdish schools have taught this view for many years, even decades now,

convincing the Kurdish people of this myth. Western reports, articles and books

played an important role in this process. Thus, Kurdish intellectuals and the

Kurdish people have grown resentful that Arabs and Turkmen have occupied and

still live in their historic homeland.

- Kurdish parties have succeeded in

casting doubt on the identity of the Turkmen regions and many other areas in

northern Iraq by including them among the disputed territories in the Iraqi

constitution, enshrining them in the constitution of so-called Kurdistan, and

including them on their own official maps.

- The Kurdish authorities rejected all

attempts by Turkmen politicians and parties to involve the Turkmen at

checkpoints at the city's entrances and exits. As previously mentioned, they

refused formation of armed Turkmen factions to protect the Turkmen, and they

also refused the entry of any Iraqi forces into the district to protect them.

- All Kurds, including the Peshmerga and

security forces, Kurdish police, all Kurdish employees, and all Kurdish

families, left when the Iraqi army entered the city, and all Kurdish neighbourhoods became empty, fearing reprisals.

True,

all these reasons at this stage are speculations, however plausible and

credible. These do not (yet) constitute definite proofs that particular

Kurdish individuals, units and institutions directly planned, ordered,

executed and participated in all these violent incidents against the Turkmen in

Tuz Khurmatu and other Turkmen areas, particularly in Kirkuk Governorate. These

reasons offer circumstantial evidence at best.

Therefore,

additional research needs to be done to identify—and prosecute at local,

national or international courts—those truly responsible for these crimes

against the Turkmen, irrespective of their Kurdish or any other identity.

Western

sources and pro-Kurdish bias

There

are several reasons for the West's embrace of the Kurdish cause. These include

the West's search for strategic partners in a sensitive region like the Middle

East, the Kurds' openness to the West, their status as one of the world's

largest ethnic groups without their own (ethno-) nation state, and they were

subjected to fierce attacks from the countries in which they revolted and

rebelled against the state.

The

Kurds' association with the ancient peoples of the Zagros region, their robust

nature, the beauty of their lands, and the charm of their terrain, which

includes towering mountains and rugged valleys, have attracted many Western travellers over the centuries, who have published their

fascinating stories about the Kurdish ethnicity. This has created a bright and

dazzling aura around the Kurds in the West, leading to increased media coverage

of the Kurds in Western literature and studies.

Decades

of Ba'ath rule followed, fostering the development of the Kurdish movement and

exposing the Kurds to repression and bloody events. This situation has led to

increased interest in the Kurdish issue by Western strategic centres, and numerous reports, articles and studies have

been published on the Kurds, their history, geography, suffering, and cause.

Because Iraq was not open to field research, most of these publications

interpreted, and sometimes distorted, facts to favour

the Kurds. In other words, Western interpretations of the region's events,

politics, history, and geography were influenced by their focus on the Kurdish

issue at the expense of other Iraqi communities, especially the Turkmen, who

constitute a vast geographic area and a significant proportion of the

population.

The

prioritisation of national interests in Western

foreign policies, often at the expense of values of justice and human rights

established by Western societies, naturally reinforces the conspiracy theory

prevalent in non-democratic societies about the treatment and intentions of

Western states toward their societies and countries. This is manifested in

questioning the intentions and behaviour of all

Western governmental and non-governmental institutions in those countries. One

reason for this is that state control over all areas of administration and much

of social life is normal in non-democratic cultures.

This

phenomenon is clearly evident in the West's handling

of the Kurdish issue. The majority of peoples

suffering from the Kurdish problem, such as Iraqis, Turks and Syrians, believe

that Western countries, with all their institutions, are biased toward the

Kurds and support them in achieving national strategic gains. These peoples

believe that the news, reports and research published by Western media outlets,

civil society organisations, and universities are

deliberately prepared according to this strategy and represent a Western

positive bias in favour of the Kurds.

Addressing

these unconstructive perceptions in non-democratic cultures is essential to

improving their perceptions of the democratic system and human rights

principles. This will undoubtedly contribute to positive interaction between

these societies and Western culture and their countries eventually.

Regarding

the relevance of this phenomenon to the subject of this study, it is clear that

the thousands of reports and studies published by Western media, human rights organisations, and universities on the subject of the study

did not reflect even a small part of the reality of the tragedies suffered by

the Turkmen in Tuz Khurmatu and Kirkuk too at the hands of Kurdish parties and

Peshmergas over the fourteen years covered by this study.

Furthermore,

Western communities have been preoccupied with the Kurdish issue for nearly a

century, which has been reflected in their policies and treatment in favour of the Kurds, despite the presence of other major

communities in Iraq that, like the Kurds, were subjected to the most horrific

human rights violations under the Ba'ath regime.

Nor

did Western sources ever address the inability of the Peshmerga militias as an

unprofessional military force, especially in such circumstances when the

central state and all its institutions were absent, given that the Iraqi

government had declared its inability to protect the Turkmen for most of the

period covered by this study (Minority Rights Group International 2014: 6, 14).

Western

studies have not demonstrated the Kurdish parties' unbridled desire to

establish a Kurdish state and the permissibility of using all the available

means to achieve this. In the photo shown further below (Photo 1), published on

a German news website in September 2014, Kurdish Peshmerga forces are shelling

the large Turkmen village of Bastamli from an

isolated angle, claiming that ISIS is there. Under the prevailing conditions in

the region at the time, the Kurdish Peshmerga forces, the only armed force in

the district, could not be absolved of the daily artillery shelling that

targeted Tuz Khurmatu and dozens of Turkmen villages in the district for years

(Bickel 2014).

It

is worth noting that the Kurdish parties and Peshmerga forces were Kurdifying Tuz Khurmatu and all areas of northern Iraq,

especially those belonging to minorities, without the Iraqi government and

coalition forces taking any action to prevent this. A report of the Middle East

Centre of London School of Economics and Political Science mentioned the

followings "The Kurds, who took advantage of US backing and occupied the

buildings of the former Iraqi regime. They held the office of the mayor and

other key positions and sought to administratively align the city with Kirkuk

over and above Tikrit. Ultimately, they filled the political and governmental

vacuum in the district, leaving the large Turkmen and Arab communities of Tuz

Khurmatu mostly powerless … When the Turkmen and Arabs began to complain about

the 'Kurdification' of Tuz Khurmatu in 2004 and 2005,

US forces and administrators took limited measures to balance out the local

distribution of power" (Skelton 2019: 17).

Regarding

the Kurdification of the Turkmen regions, a report of

the international Crisis group mentioned the following: "Unwilling, for now, to

cross its most reliable Iraqi allies, Washington has largely stood silent in

the face of Kirkuk's progressive Kurdification; to

lessen tensions created by the flood of displaced Kurds coming to the town, it

also has launched wide-scale countryside rehabilitation. Moreover, it provides

technical support and indirect funding to the Iraq Property Claims Commission.

When accused of aiding Kirkuk's Kurdification,

officials reportedly replied that other communities were free to bring their

people into the town" (International Crisis Group 2006: 2).

If

we take the numbers of Western publications and sources about the Kurdish issue

in Iraq, we find that these are hundreds of times greater than the numbers

published about other Iraqi minorities, especially the Turkmen, whose suffering

was not much less than the suffering of the Kurds, and whose population (9%)

was not much less than the population of the Kurds (13%) (Knights 2004: 262;

Shah 2003: 4).

Photo

1 Peshmerga artillery shelling the

Turkmen village of Bastamli, south of Tuz Khurmatu

District

Source:

Markus Bickel, 'Kein Schneller Krieg (No Quick Victory)' Frankfurter Allgemeine

Zeitung, 9 May 2014.

It

has become clear today that the deliberate dwarfing of the Turkmen population

number in Iraq by the British Mandate of Iraq and the Iraqi monarchy when the

Iraqi Kingdom was established after World War I was for geopolitical reasons.

The

preliminary results of the 1957 census, which many Western authorities

considered closer to reality in terms of the size of Iraq's small constituents

(minorities), but which the Turkmen rejected, showed that the total Turkmen

population in Iraq was 136,806 (Al-Zubaidi 1981: 28). It should be noted that

the General Directorate of Population, which conducted the 1957 census, was

affiliated with the Ministry of Interior (General Directorate of Population

1957), and Saeed Qazzaz, a Kurd from Sulaymaniya, was the Minister of Interior (Saleh 2010:

309n16). However, the revised results of the same census, issued in 1958, when

the minister had changed, showed that the total Turkmen population in Iraq was

567,000 (Knights 2004: 262; Shah 2003: 4).

According

to the General Directorate of Population, the initial results of the same

census estimated the Kurdish population in Kirkuk Governorate at 48.3% (General

Directorate of Population 1957: 243). The Kurds rely on these results in their

claims to ownership of Kirkuk Governorate and its inclusion in the Kurdish

region (Kane 2011: 5). However, revised results of the same census, as

mentioned above, showed that the Turkmen population in Iraq was approximately

four times higher than the initial results. This increase in the Turkmen

population did not apply to the city and governorate of Kirkuk, which would

undoubtedly have led to a decrease in the proportion of Kurds in both the city

and governorate.

It

is worth noting that the 1957 census estimated the number of Kurds in Iraq at

about 900,000 people (13%) of the total populations of Iraq (Knights 2004: 262;

Shah 2003: 4). However, today the Kurds, with all their administrative,

political and academic authorities, along with Western sources and references,

exaggerate the number of Kurds in Iraq, sometimes to the extent of 25% (Jongerden 2016: 1; Bengio 2017: 15; Lasky 2018: 1), and

thus they obtain privileges and gains from the Iraqi state by inflating their

percentage of the total population of Iraq.

However,

all but two or three Western publications (Knights 2004: 262; Shah 2003: 4)

ignore the revised census results and solely cite the preliminary results,

which underestimate the size of the Turkmen population in Iraq by approximately

four times. The adjusted results for individual Turkmen regions, particularly

Kirkuk, have not been published, as the Kurdish claim to Kirkuk is based

primarily on the preliminary erroneous results of the 1957 census, which

logically suggests that the Turkmen population in Kirkuk at that time was

deliberately dwarfed fourfold.

Any

researcher of the geography of northern Iraq can easily notice the widespread

presence of Turkmen, whose vast lands extend across all northern governorates,

including Salah al-Din, all of Diyala and even Kut

governorate. Dozens of Western reports on the massive displacement of people

during the rise of ISIS reveal a significant Turkmen presence among displaced

families throughout northern Iraq, including Diyala and Salah al-Din provinces

(United Nations Development Programme 2018: 33,

66-67, 29-30).

A

quick look at Iraq's history, and the sources are multiple, indicates that the

mass Kurdish migration from the east to Turkmen regions is not ancient, having

increased significantly only since the 1930s. However, most Western reports and

other research outputs do not address this issue. Rather, many consider Turkmen

regions, such as the Kifri district and the city of

Erbil, where the Kurdish population subsequently increased, to be historically

Kurdish regions.

In

the same context, many Western reports consider Tuz Khurmatu a Kurdish region

or mention Kurds first when mentioning its components—even though Turkmen still

constitute the majority (65%) in Tuz Khurmatu (Kirkuk Now 2024).

So

overall, information can be found distorted in favour

of the Kurds in most Western reports. To take just example among numerous, Vice

Media mis interpreted the barriers built by the Turkmen to repel attacks as

barriers to protect the Kurds from snipers (McDiarmid 2016).

According

to a report by the International Crisis Group, "During 2003-2017, the city of

Tuz saw frequent clashes between Kurdish parties … and Turkmen parties ... . Tuz's Kurdish residents fled, and the Hashd wrought

major destruction on Kurdish property. Backed by the Hashd, local government

administrators sacked Kurdish public employees who did not return, replacing

them with Turkmen" (International Crisis Group 2018: 16, 17).

In reality, the

Turkmen were defenceless, exposed to daily terrorist

attacks, and unable to confront the three Peshmerga brigades and the

exclusively Kurdish security and police forces that controlled the city.

Moreover, after the formation of the Turkmen armed factions in 2014, three

clashes with the Peshmerga occurred there, up until 2017. This study already

has provided details of these clashes elsewhere, and the commentary on the

Amnesty International report in the following paragraph provides details of the

Kurds' flight from the city after the arrival of the Iraqi army and the damage

inflicted in their areas, and how it was exaggerated.

An

Amnesty International report on the Iraqi army's entry into Tuz Khurmatu in

October 2017, which must have been transmitted by the Kurds, clearly distorts

the facts in favour of the Kurds. The report states:

"It looked like 90% of the buildings in al-Jumhuirya

were burned ... . Those who had returned briefly to

the city reported seeing extensive damage to homes in al-Jumhuriya

and Hai Jamila, both Kurdish-majority neighbourhoods".

In the article, Amnesty International published a satellite image of part of

Tuz Khurmatu showing some red and black spots to support its claims. It did not

give any title for the image other than to indicate some of the black spots,

claiming these were smoke rising from burning Kurdish homes. However, the

locations of the red and black spots in the image are overwhelmingly in Turkmen

areas. The image also shows the al-Jumhuriya neighbourhood mainly populated by Kurds, where there are

almost no black or red spots (Amnesty International 2017 (incl, quotes); see

Photo 2 further below). As usual, the Kurdish media distorted the facts even

further (Rudaw 2017).

As

mentioned above, the reliance of Western authorities, including academics, on

politicians, intellectuals, Peshmerga fighters, and other Kurdish actors as

sources of information about Iraqi minorities, especially the Turkmen, is one